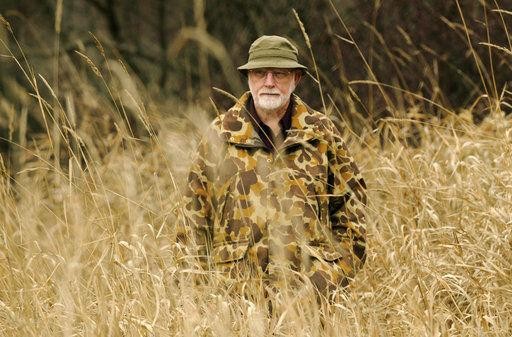

BOISE, Idaho (AP) — Patrick F. McManus, a prolific writer best known for his humor columns in fishing and hunting magazines who also wrote mystery novels and one-man comedy plays, has died. He was 84.

McManus died Wednesday evening at a nursing facility where he lived in Spokane, Washington, where he had been in declining health, Tim Behrens, who performed the one-man plays, said Friday.

“He was a warm man, he was a good man, he was a funny man,” Behrens said. “I look at him right up there with Mark Twain.”

McManus wrote monthly humor columns for more than three decades for the popular magazines Field & Stream and Outdoor Life, the columns later appeared in books. He also wrote other books, more than two dozen in all that included a guide for humor writers, and a series of mystery novels with a darker form of humor involving fictional Blight County, Idaho, and Sheriff Bo Tully. Altogether, he sold more than 5 million copies and appeared on the New York Times best-seller list.

Many of his characters are drawn from real people from his childhood in Sandpoint, Idaho, about 75 miles (120 kilometers) northeast of Spokane, said Bill Stimson, a journalism professor at Eastern Washington University and former writing student of McManus at the same school. The two became lifelong friends.

The fictional Rancid Crabtree, for example, is a loner living in the woods who only cares about fishing and hunting and has no one telling him to go to school. Stimson said McManus told him that Crabtree is based on a real person that he found in the hills around Sandpoint as a child.

While many of his characters involve country bumpkins, McManus himself loved reading.

“He had a very scholarly interest in writing and literature,” Stimson said. “He read everything.”

He said McManus quit teaching in 1983 to write full time. He had been writing traditional journalism pieces until on a fluke he wrote a humorous piece about satellites tracking wildlife, Stimson said, that a magazine immediately bought.

“He was a very accomplished journalist to begin with, and then he found out he could make a lot more money as a humorist,” Stimson said. “He’s really the Mark Twain of the Northwest.”

McManus was also an accomplished painter, favoring watercolor landscapes, his wife Darlene McManus said in a prepared statement.

“Pat was a great observer of people. I think this was because he was an artist at heart,” Darlene said. “His stories were paintings with words.”

Patrick Francis McManus was born in Sandpoint on Aug. 25, 1933. His father died when McManus was 6.

“I can remember the isolation of living out on a little farm and everything being extremely hard and miserable,” he told Sandpoint Magazine in 1995. “But I don’t tend to think of it that way, and I think it’s because of the writing and transforming my early situation.”

Behrens said being poor during childhood was reflected in McManus’ writing.

“The lack of any kind of extravagance led to the ability to create entire imaginary worlds out of his walks in the mountains,” he said.

McManus, Stimson said, nearly flunked out of Washington State University but then got serious about writing, and remained so for the rest of his life, dedicating a certain part of each day to writing and telling his students to do the same.

Behrens has performed the six one-man plays McManus wrote for more than two decades. He said McManus would attend the early plays and listen to the audience reaction, then make changes to the play until he was satisfied.

“He would walk in the back of the theater, never sitting down,” Behrens said. “He would listen, and he would pace, and he would think. It took about 50 shows before one was set.”

McManus is survived by his wife, Darlene, four daughters, nine grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

A private service is tentatively planned for next week at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Sandpoint.